Alfred Batlle-Fuster

THE THEORY OF INFINITESIMAL ETERNITY: A NEW VISION OF TIME AND ETERNITY

The Theory of Infinitesimal Eternity (TIE) presents a bold and disruptive conception of two fundamental notions in the history of thought: time and eternity. Philosophically, eternity is often treated as an absolute, immutable, and transcendent state, while time is understood as a finite flow—dynamic, fleeting, and limited to human experience. The TIE, however, dismantles this classical dichotomy, proposing that eternity is not a static reality situated outside of time, but one that is intimately interwoven with every instant of existence.

The Theory of Infinitesimal Eternity introduces a key concept that revolutionizes our understanding of eternity: it conceives of it as a mathematical limit that tends toward zero infinitely, thereby transforming the traditional notion of eternity into something dynamic and fluid. This perspective stands in stark contrast to Plato’s vision, in which eternity was conceived as a world of immutable, perfect Ideas, entirely separate from time and sensory experience. The TIE, by suggesting that eternity can be viewed as a series of infinitesimals approaching zero—that is, non-time—yet never fully reaching it, opens the door to a conception where time and eternity are not opposing entities but interdependent.

Here, each temporal instant becomes a vessel containing fragments of eternity, though in an infinitesimal and continuously diverging form—a proposition that resonates with Henri Bergson’s ideas on duration. Yet the TIE goes further, emphasizing that we do not merely experience time, but actively create it. Furthermore, the TIE’s proposal may be compared to Immanuel Kant’s notion of time as a form of pure intuition, where temporality is essential to our experience of the world. However, unlike Kant—who regarded time as a static framework for perception—the TIE posits that it is a process in constant evolution, intrinsically bound to life itself.

In this semantic reconfiguration, eternity ceases to be a distant destiny or an ideal state, becoming instead an inherent element of human experience. Thus, each moment of life is a manifestation of the eternal that, though finite, contains the essence of the infinite—challenging the view that time and eternity are mutually exclusive. In this sense, the TIE not only redefines eternity but also invites us to rethink our relationship with time, life, and death. It proposes an existence where the ephemeral and the eternal are inextricably intertwined, and where every second lived becomes an affirmation of infinity in its most delicate and subtle form.

TIME AS THE INVENTION OF LIFE

Within the framework of the Theory of Infinitesimal Eternity, time cannot be conceived as an external, preexisting structure independent of life, but rather as life’s constant invention—an intrinsic product of its very manifestation. Every living being, by existing, becomes an active creator of time, an artificer who forges finite chronology as they live and experience, thereby generating a dynamic response to immutable eternity. While eternity remains a stable and indifferent backdrop—an infinite, static presence underlying all that exists—life, in its fleeting eruption, momentarily ruptures that eternal continuity. In living, life generates the temporal: it creates instances, seconds, and moments, finite structures that give rise to becoming, succession, and change. Each vital instant is a victory over eternity, an act of creation amid an ocean of infinitude, a fluctuating play between the time invented with each breath and the eternity that surrounds it, threatening to absorb it once again into immutability.

Life, in its flow, does not merely inhabit time but actively generates it, producing it as it expands and unfolds. Time is not revealed as an external entity regulating the processes of life, but as something that springs forth from life itself, configured in the tension between the finitude of existence and the infinitude of the eternal. Thus, every living being, in its mere existence, is both a creator and a destroyer of time: engendering it with each instant of life, and consuming it with each step toward death.

Finite time may be understood as a juggler’s game, a precarious and continuous dance unfolding at the edge of the abyss of non-time. From this perspective, time is not a linear succession of measurable instants governed by physical laws, but rather a subtle and fragile resistance against eternity, which stretches toward absolute void. Each second, each moment of existence, functions like a sphere tossed into the air in the act of juggling—a temporal fragment defying the gravity of infinitude and the abyss of the eternal, striving to remain in balance and in motion amid the overflow of non-time. This juggling metaphor illustrates the dynamic and vulnerable nature of finite time, which struggles to sustain and perpetuate itself in its constant interaction with eternity. Finite time, in this vision, is not a solid or immutable entity, but a series of delicate, momentary movements—cast into the air of experience, shifting in unstable equilibrium, never reaching the total void of non-time, but always approaching it. In each turn, in each oscillation of the temporal sphere, the complexity of time as continuous, active creation is revealed: a perpetual act of resistance and adaptation in the face of the immutable infinite that surrounds it, a juggler’s game in which life and time intertwine in a ceaseless challenge to eternity.

Every second of life is an ephemeral yet meaningful victory over eternity, a creative act through which existence unfolds and asserts itself against the immensity of non-time. In this framework, living is not a mere passive experience of passage through time, but an active process of invention, where each instant is a triumph over the inertia of the eternal. Eternity, understood as a static and indifferent backdrop, tends toward the dissolution of all that is particular and contingent, but life, in its constant becoming, interrupts this tendency, introducing temporal fragments that resist that absolute state. With each heartbeat, life conjures time, sculpting finite moments that, however brief, represent an affirmation of temporality against eternity. This unfolding of existence is not a mere prolongation of being in time, but a creative act through which the finite takes form and meaning—becoming unrepeatable moments that rise up against the vastness of the eternal. Each second lived is, in this sense, a small yet constant rebellion against absorption into eternity, a spark of life refusing to be wholly subsumed by the eternal and immutable. Without life, time would have no meaning, for it is life that invents, organizes, and experiences it.

This vision recalls the philosophical notions of thinkers such as Henri Bergson, who distinguished between chronological time and lived duration, arguing that the true experience of time is qualitative rather than merely quantitative. Bergson maintained that lived duration reflects the richness of human experience, emphasizing that lived time cannot be reduced to mechanical or scientific measures. Yet the Theory of Infinitesimal Eternity goes beyond this duality by positing that each temporal moment inherently contains a fraction of infinitesimal eternity. This conception suggests that time and eternity are not opposing concepts, but are continuously and indivisibly interrelated—where the eternal inscribes itself into every temporal instant. In this way, each lived experience becomes a unique manifestation of the eternal, and each temporal instant echoes an infinitude unfolding in the present. This transforms our understanding of time into a richer, more complex dimension, where eternity is not perceived as a mere abstraction but as an integral part of temporal experience.

An example that illustrates this interrelation may be found in the work of philosopher and cultural theorist Susan Sontag, who, in her essays on aesthetic experience and the perception of time, argues that works of art can capture moments of lived duration that transcend chronological time. Sontag suggests that the appreciation of art allows individuals to experience a form of eternity within the immediacy of the moment, where each observation and interpretation reveals deeper dimensions of existence. Just as the TIE proposes that each instant contains a fraction of infinitesimal eternity, Sontag posits that aesthetic experience enables people to connect with a reality that extends beyond mere temporal succession, showing how art becomes a vehicle for experiencing the eternal through the ephemeral. In this light, art emerges not only as an object of contemplation but also as a medium that facilitates the encounter with the eternal in everyday life, suggesting that aesthetic appreciation becomes an act of resistance against the inexorability of time. Both perspectives, though from different vantage points, highlight the possibility that the eternal is present in every moment of lived experience, thereby enriching our understanding of time and human existence.

Walter Benjamin, particularly in his work The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, argues that the technical reproduction of art transforms aesthetic experience, allowing the spectator to access moments that were once ephemeral and, in turn, revealing the temporality of the historical and cultural context. Like Sontag, Benjamin suggests that through reproduction and the recontextualization of art, a space opens where the eternal can be encountered in the perception of the present. His idea that art can condense and transform temporal experience also aligns with the TIE, suggesting that lived moments can be reconceptualized to reveal something deeper that transcends mere chronology. Both perspectives, through their attention to aesthetics, invite us to explore how the experience of time can serve as a space of connection with the eternal, generating a more complex understanding of life and its relationship to temporality.

DEATH AND THE RETURN TO INFINITESIMAL ETERNITY

In the classical conception of philosophy, death is understood as the threshold separating temporal existence from a transcendent and immutable eternity. From Plato’s reflections, who saw death as the liberation of the soul from the body and its return to the eternal world of Ideas, to the Christian tradition, where death was conceived as the passage into a definitive and absolute eternity, the common view has been that time ends at the moment of death, giving way to an eternity beyond time. The Theory of Infinitesimal Eternity radically reformulates this transition: rather than conceiving death as an abrupt rupture between the temporal and the eternal, the TIE suggests that death is a continuous transition toward a form of infinitesimal eternity—that is, an eternity that unfolds asymptotically within time itself. This notion may be read as a response to Kant’s paradox in the Critique of Pure Reason, where time and space are a priori forms of human sensibility, cognitive structures that order our experience of the world but do not exist beyond it. By conceptualizing eternity not as a reality external to time but as an infinitesimal process toward non-time, the TIE suggests that death is not an escape from these sensible forms but rather an integration of the eternal into the temporal—an infinitesimal extension that cannot be perceived or comprehended. The idea recalls Hegel’s vision of the dialectic between the finite and the infinite, where the finite does not vanish into the infinite but is reconciled with it in a higher synthesis. Yet the TIE departs from Hegelian dialectical resolution by introducing a mathematical perspective: death does not dissolve the subject entirely into the eternal but instead extends it infinitesimally, without ever reaching “non-time.” The TIE thus offers a vision in which death is not a final terminus, but a process of continuous incompletion, close to Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenology, which emphasized that the experience of the body and of time is always unfinished. Here, death is not an end but a limit never fully reached—a state of transition toward an eternity that, in its infinite minuteness, remains an unattainable horizon, granting life itself a dimension of active transcendence in which every instant remains, infinitesimally, a part of the eternal whole.

At the moment of death, life’s time appears to cease, yet the Theory of Infinitesimal Eternity posits that this cessation is never complete. At death, the time of a life begins to be depleted infinitesimally, an asymptotic process in which life approaches the limit of non-time but never fully reaches it. From this perspective, death does not entail the definitive extinction of time, but rather an infinitesimal exhaustion that continues indefinitely. This introduces an understanding of death that challenges traditional notions of finitude and absoluteness, suggesting that what appears to be the end of life is in fact a continuous transition toward a state of existence sustained endlessly. Death thus becomes a process that affects not only the individual who dies but also reverberates in the time that follows, implying that the imprint of that life continues, however infinitesimally, perpetuating the person’s existence in the fabric of time. This approach also invites reflection on how we remember and live with the lives of those who have passed, suggesting that their presence persists in the memory and experience of those who remain, as fragments of eternity unfolding in every recollection and every narrative.

The work of philosopher and writer Alain de Botton, particularly in The School of Life, explores how our experiences and memories of those who have died can continue to influence our daily lives. De Botton argues that the death of a person does not simply mark an abrupt rupture in our relationship with them; rather, the memories and lessons we have drawn from that person continue to shape our decisions and feelings in the present. Just as the TIE suggests that time is never fully exhausted with death, De Botton highlights how a person’s legacy persists in our lives, shaping our interactions and memories. Both perspectives emphasize the idea that, although physical life may cease, the essence of that existence remains alive in the memory and emotional impact it leaves behind—resonating with the notion that death is a process of infinitesimal depletion, not an absolute end.

This concept of death introduces a radically different vision of eternity. Life, even after its chronological end, retains an infinitesimal fraction of time that prevents it from dissolving entirely into absolute eternity. In this way, life does not extinguish but persists infinitesimally in a continuous process of withdrawing from the threshold of the eternal. This approach echoes mathematical notions of the infinitesimal, where a function may approach a value infinitely without ever reaching it—suggesting that the essence of life persists in a constant approximation to eternity without ever fully fading. Thus, each lived life, though it ends, becomes a fragment that remains present within the continuity of time, challenging the idea that death entails an absolute termination. This reinterpretation of death also invites reflection on how the meaning of our life experiences extends beyond physical existence, positing that every moment lived contributes to an eternity manifested infinitesimally in memory, relationships, and the legacy of each individual.

Judith Butler, in Frames of War, explores the fragility of life and the importance of collective memory in the construction of identity and resistance. Butler argues that, although lives may be cut short by violence or injustice, their impact persists in the narratives created around them, shaping the culture and politics of the present. This perspective shares with the TIE the notion that, although physical life may conclude, its legacy endures within collective consciousness, allowing a fraction of that existence to continue influencing the world. Thus, both Butler and the TIE suggest that death is not simply an end but a point of transition, enabling the essence of life to be preserved and manifested in ways that transcend temporality, reflecting the complexity of being and its relation to eternity.

DYNAMIC ETERNITY AND THE CREATION OF TIME

One of the major contributions of the Theory of Infinitesimal Eternity is the notion of a dynamic eternity which, unlike the classical Platonic vision of a fixed and transcendent eternity—situated in a world of immutable Ideas beyond time—manifests itself within time itself. Each instant of life, rather than being a mere fragment of a linear temporal becoming moving toward oblivion, contains an infinitesimal fraction of eternity, much like Henri Bergson’s distinction between chronological time and “lived duration,” where the subjective experience of time has an irreducible and immeasurable quality. Unlike traditional notions that conceive eternity as an absolute and immutable state, the TIE posits that eternity is a continuous process, in constant approximation to non-time yet never reaching it, evoking the paradoxes of the infinite proposed by Leibniz and Zeno. In this way, eternity becomes a perpetual movement, always present but never fully accessible, and establishes a convergence with more contemporary theories such as those of Gilles Deleuze, who conceives of time in two planes: chronological time, which unfolds in the present, and eternal time or “Aion,” which is a becoming that cannot be fixed in any given moment but is always unfolding. By intertwining the eternal and the temporal, the TIE opens a new path for thinking about human finitude within a framework in which time is not opposed to eternity, but instead contains it infinitesimally within each of its moments.

Time, according to the Theory of Infinitesimal Eternity, appears as a finite manifestation of eternity—an idea aligned with philosophical concepts that have sought to reconcile the temporal and the eternal in diverse ways. In contrast to Heidegger’s vision of time as the horizon of human existence, where being is defined in relation to finitude and to “being-toward-death,” the TIE suggests that each lived moment is in fact a temporal expression of the eternal—an infinitesimal fraction that, though limited, contains within itself a spark of the infinite. The idea recalls Plotinus, who described time as a “moving image of eternity,” yet where the TIE diverges is in its insistence that time is not a shadow or mere reflection, but an active and ongoing creation of the eternal. Each second of life is not simply an inevitable transition toward death, but a creative and perpetual materialization of eternity, akin to Nietzsche’s affirmation of the “eternal return,” in which every moment repeats infinitely, endowing life with an eternal character. However, while Nietzsche frames eternal repetition as a closed and cyclical recurrence, the TIE introduces a perspective in which each instant is a unique act of resistance against the abyss of the eternal—not as repetition, but as the creation of a new and irreducible time.

Time is the process through which eternity fragments into lived instants. Life, by creating time, challenges absolute eternity, generating a temporal continuity that, though finite, is never entirely exhausted. This phenomenon suggests that every moment of existence is an expression of the eternal, manifesting itself in the subjective experience of living. The TIE proposes that each instant contains a spark of eternity, rather than viewing time as a mere succession of isolated events—implying that the act of living not only unfolds within time but also functions as the medium through which the eternal expresses itself. Thus, eternity becomes a dynamic context fragmented into particular experiences, where the finitude of life is, in fact, an act of resistance against total dissolution into the absolute. This approach not only redefines temporality as an active element of existence, but also invites a reconsideration of how we value our experiences and how we relate to the notion of eternity, making it accessible through every lived moment.

THE PARADOX OF BEING INFINITESIMALLY ETERNAL

One of the most fascinating and disruptive aspects of the Theory of Infinitesimal Eternity is its bold claim that, although our lives are finite in terms of chronological time, we are eternal in an infinitesimal sense. This vision clashes with traditional philosophical conceptions that draw a sharp division between the finitude of life and transcendent eternity, such as in the thought of Thomas Aquinas, who conceived temporal life as a finite prelude to definitive and complete eternity in union with God, or in Epicurus’ view, which held that death was simply the end of sensation, dissolving any continuity between time and eternity. In contrast, the TIE proposes that, even though our existence is bounded by chronological time, each instant of life contains an infinitesimal fragment of eternity—implying that life, in its temporal manifestation, never fully extinguishes itself. This eternal fragment is not an absolute eternity existing outside of time, but rather an eternity that, through an asymptotic process, continues to exist infinitesimally even after death. This approach partly recalls Baruch Spinoza, who argued in his Ethics that the human being, as part of the infinite substance that is God or Nature, participates in eternity through the intellect, even though body and imagination remain bound to temporal finitude. Yet the TIE distinguishes itself from Spinoza by not conceiving eternity as participation in something transcendent, but as an inherent property of every instant of time that, however infinitesimally small, is eternal by its very nature. This perspective also resonates with Heraclitus’ notion of constant flux, where permanence is change itself; but within the TIE, temporal flux is not only a dynamic process, but also a manifestation of the eternal within each fragment of time.

The idea that life never completely extinguishes, because each instant contains a portion of eternity, also stands in opposition to the vision of Arthur Schopenhauer, for whom life is merely the temporal manifestation of a “will” that, after the individual’s death, dissolves once again into the impersonal and the timeless. Rather than proposing a dissolution into nothingness or into an impersonal totality, the TIE suggests that the temporal and the eternal are intertwined in such a way that life continues to exist infinitesimally even after death, in a continuous process of approximation to the eternal without ever fully reaching it. Conceiving of eternity as something that persists infinitesimally in time opens a new dimension for reflecting on the meaning of life and death, for human existence is no longer seen as something with a clear beginning and end, but as a process that, though finite, contains a fraction of the eternal that never fully vanishes. In this interpretation, the TIE becomes a theory that redefines the relationship between time and eternity, aligning itself with contemporary visions such as Derrida’s idea of writing as a trace that always survives the present moment, or Deleuze’s conception of becoming as something always unfinished—implying that life, though finite in temporal duration, always contains a vestige of eternity within its continuous and divergent unfolding.

This vision introduces a paradox: according to the Theory of Infinitesimal Eternity, we live eternally—but in an infinitesimal way—radically altering traditional conceptions of eternity and finitude. Unlike classical notions of eternity as something grand, absolute, and immutable, as in Parmenides, who affirmed that what is true and eternal is immobile, unchanging being, or Plotinus, who described eternity as the perfect state of immutable Unity beyond time, the TIE suggests that eternity does not manifest itself in absolute totality but in small fragments that dissolve into the finite time of life. This dissolution is not a disappearance, but an infinitesimal dissolution, in which finite life never exhausts itself but continues to exist in a process of approximation to non-time without ever reaching it. This paradox broadly recalls Leibniz’s idea of monads: indivisible and eternal units that, although infinitely small, constitute reality as a whole. However, while Leibniz’s monads are complete in themselves and do not interact with one another, the TIE posits that every fragment of lived time contains a small portion of eternity—a fragment that, though infinitesimal, remains part of an infinite temporal structure.

On an ontological level, the TIE can also be linked to Bergson’s notion of duration as an experience of time that cannot be reduced to mere measurable units, but rather constitutes an indivisible continuity. Yet the TIE goes further by suggesting that this continuity is populated by infinitesimals which, in their very smallness, contain a form of eternity. This fragmentary and subtle eternity breaks with the tradition of identifying the eternal with what is transcendent and immense, as in Aquinas or Heidegger—who held that authentic temporality reveals itself in finitude, in being-toward-death, where death discloses the totality of existence. In the TIE, by contrast, death does not reveal an absolute end but rather a transition toward an infinitesimal eternity, a state in which life, though finite, continues projecting itself toward non-time without ever attaining it. This conception is also profoundly different from Sartre’s, who viewed existence as radically finite and contingent, condemned to vanish into the void of death. The TIE, in suggesting that finite time never fully exhausts itself, grants us a form of eternity that is not immense or immutable but small, subtle, and fragmentary—yet nonetheless real and enduring. This infinitesimal eternity transcends both traditional notions of eternity and existentialist conceptions of radical finitude, offering instead a perspective in which life continues beyond its own finitude, perpetually sustaining itself in a state of approach toward non-time—a process without end that thereby secures us a form of immortality that is neither grand nor visible, but remains a fundamental ontological fact.

Human beings are not condemned to vanish in death; rather, according to the Theory of Infinitesimal Eternity (TIE), they persist in infinitesimal suspension—an existence which, although finite in chronological terms, never reaches extinction in non-time. This concept introduces a radically different vision of human mortality compared with many philosophical traditions. Whereas Epicurus asserted that death is simply the total cessation of existence—“where I am, death is not; where death is, I am not”—the TIE suggests that although we are not consciously or chronologically present after death, an infinitesimal form of our lived time persists within an atemporal structure. This view also challenges Nietzsche’s nihilism, which saw life as an eternal cycle of repetition in which death offers no meaningful transcendence but only reiteration of the same in eternal recurrence. By contrast, the TIE posits that every life, though finite, leaves behind an infinitesimal trace that continues to exist within a continuum of diminutive eternity.

We may also contrast this with Kant’s vision, who understood time as an a priori form of intuition, a necessary condition for human experience, but always finite. The TIE, in suggesting that eternity infiltrates every instant of time, reformulates this Kantian conception by proposing that time is not merely a limited framework for experience, but a field where the eternal coexists with the temporal. This coexistence of finitude and eternity departs both from existentialist conceptions—such as Camus’, for whom life is absurd and death final and inevitable—and from Heidegger’s being-toward-death, where death is the event that gives existence its meaning. Instead of viewing death as the absolute end of life, the TIE interprets it as a threshold toward infinitesimal suspension, where life is not a mere sequence of finite moments extinguished at the end, but rather a fabric of tiny eternities that endure beyond chronological closure.

This vision brings us closer to a reinterpretation of Hegel’s notion of overcoming finitude through Absolute Spirit, though in the TIE this overcoming is not a process of dialectical synthesis but a constant dissolution of the temporal into the infinitesimal eternal. Life does not abruptly dissolve into death, as existentialist philosophies suggest, nor does it attain a transcendental, immutable eternity, as in classical religious or metaphysical traditions. Instead, it sustains itself in a continuous and delicate process in which fragments of finite time intertwine with a miniature eternity—suspended infinitesimally between being and non-being—creating a dispersed yet present immortality.

TOWARD A NEW UNDERSTANDING OF LIFE, TIME, AND ETERNITY

The Theory of Infinitesimal Eternity (TIE) profoundly redefines the relationship between life, time, and eternity, proposing an innovative conception in which eternity is not an absolute and transcendent state separate from time, but rather a continuous process unfolding through temporal instants. This approach offers a radical break from the classical dichotomies of Western philosophy, which have treated eternity and time as two separate and irreconcilable dimensions—from the Platonic vision of the immutable and eternal “world of Ideas” to Aristotle’s notion of time as the “number of movement according to before and after.” Whereas Aristotle saw time as a measure of change in the sensible world—limited and finite—and later thinkers such as Thomas Aquinas maintained that eternity was the exclusive domain of God, an immutable being outside of time, the TIE challenges this separation, suggesting instead that eternity is not beyond time but interwoven with it constantly and infinitesimally.

Similarly, the perspective of the TIE contrasts with Edmund Husserl’s phenomenology, which conceives of time as a structure of consciousness in which each instant is retained in memory while we anticipate the future. While Husserl describes how individual moments interconnect, the TIE goes a step further by suggesting that these moments are not merely part of a finite temporal sequence, but that each one contains an infinitesimal fraction of eternity. Here we may also draw a comparison with Heraclitus’ philosophy of becoming, which affirmed that everything is in constant flux and nothing remains, in opposition to Parmenides’ idea of a static, eternal being. The TIE reconciles these classical positions by postulating that, although life appears to move within the confines of time and change, it is connected to an eternal dimension expressed infinitesimally in each instant.

Through this lens, life is not simply a finite and contingent phenomenon, as materialist philosophies suggest, nor is it subordinated to a final destiny of dissolution into non-being, as certain existentialist perspectives maintain. The TIE invites us to consider life as a form of miniature eternity, a continuous creation of time and meaning that does not cease at death but instead persists infinitesimally, generating an inexhaustible continuity. This vision aligns with the work of Henri Bergson, who distinguished between quantitative time and qualitative “duration.” Yet, whereas Bergson upheld a distinction between measurable time and lived experience flowing in continuity, the TIE maintains that the eternal is not opposed to time but manifests within it through micro-fragments of eternity. Life not only creates and sustains time, but each second lived becomes an act of resistance and creation against dissolution into non-time, rendering human existence—far from finite—a bearer of an eternal component that prolongs itself infinitesimally. This framework reformulates our understanding of mortality and immortality, not as categorical opposites, but as interconnected realities woven into the fabric of time and being.

Each moment of life is a small victory against absolute eternity, an act of temporal invention that defies non-time. Life becomes a constant act of creation and resistance, where each instant represents an opportunity to manifest existence in a context that, though limited, never entirely extinguishes itself. Even though chronological life approaches its end in death, this process does not entail definitive extinction, for it persists as an infinitesimal fraction of time that fades indefinitely without ever reaching its absolute end. Thus, each lived moment becomes an echo of eternity, a resistance to oblivion that challenges the notion of death as the termination of experience. This approach reconfigures our understanding of life, highlighting the significance of each instant as a meaningful triumph within the vast horizon of the eternal, where the finite confronts the infinite, creating a dance of existence that continues beyond life itself.

Philosopher and writer Yuval Noah Harari, in his work Sapiens, explores how human narrative has been fundamental in constructing our reality. Harari argues that human beings have created meaning and values through stories, enabling them to face the finitude of life. Just as each moment of life in the TIE is considered an act of invention that defies eternity, Harari maintains that the narratives we create are ways of giving meaning to our existence, allowing us to transcend the banality of time and forge enduring connections. Both perspectives reflect the idea that, even though we face the inevitable end of life, our actions and stories provide meaningful resistance—transforming our experience into a fabric of meanings that unfolds beyond temporality, pointing toward the eternal, however infinitesimally.

This vision radically transforms our understanding of time, death, and the very conception of eternity. Instead of viewing eternity as a fixed, unattainable, transcendent state, the Theory of Infinitesimal Eternity invites us to recognize a form of eternity that is infinitesimal and dynamic, persisting and unfolding through every instant of life. Within this framework, each moment becomes a vehicle of the eternal, where lived experiences are not merely transitory but infused with a spark of eternity that grants them profound significance. Life itself, with all its limitations and fragilities, reveals itself as a finite manifestation of the eternal, a continuous process of creation in which every decision and every action possesses the power to converge beyond immediate time. This perspective allows us to appreciate the beauty and value of the ephemeral, underscoring that, although our lives are finite, each lived instant may capture something of that eternity which connects us to the cosmos and to life itself. In this way, eternity is not a distant aspiration but an accessible reality, here and now, present within the totality of our human experience—inviting us to live with greater fullness and awareness.

REDEFINITION OF TIME

In the Theory of Infinitesimal Eternity, time is radically redefined—not as a mere linear and chronological succession of empty instants, but as a semantic construct laden with meaning, deeply tied to life and conscious existence. The traditional idea of time as something external, objective, and independent of human subjectivity—as upheld by philosophers such as Immanuel Kant, who regarded time and space as ‘a priori’ conditions of human experience—dissolves under the TIE. In this theory, time is not an external framework within which life unfolds; rather, it is life itself that invents and sustains it. Every living being, through existing and experiencing, is not merely “within” time; instead, it generates temporal moments, making time a product of life.

This leads to a significant semantic shift: time ceases to be something fixed and preexisting and becomes instead a dynamic and infinitesimal creation responding to the vital force of living beings. This conception resonates with the ideas of philosophers such as Henri Bergson, who, in his notion of durée, distinguished between chronological time—measured and quantifiable—and lived time, qualitative and fluid. The TIE takes this distinction further, suggesting that chronological time is merely an illusion created by our need to structure experience, whereas real time, the time of life, is infinitesimal and continuous, constantly generating fragments of eternity within each instant.

This perspective also aligns with the philosophy of Martin Heidegger, who in ‘Being and Time’ argued that human life does not simply unfold within time, but that “being” already implies an intrinsic temporality. However, while Heidegger focuses on being-towards-death and on how the awareness of finitude shapes existence, the TIE suggests that life is not ultimately limited by death. Instead, it creates a time that never fully exhausts itself. Death, far from being the absolute end of time and existence, becomes a point of convergence with infinitesimal eternity—an instant in which life, though finite in appearance, continues to create time infinitesimally, perpetuating the flow of existence in a form that approaches non-time without ever reaching it.

In this regard, the TIE also diverges from the traditional concept of eternity defended by thinkers such as Plato, for whom the eternal belonged to the world of Ideas, separate from the physical and temporal realm. In the TIE, eternity is not detached from the world but is embedded in the very heart of each instant, in an infinitesimal form that dynamically connects the finite and the infinite.

The concept of time in the Theory of Infinitesimal Eternity is further enriched by the idea that every instant of life is a temporal creation arising as an active resistance to eternity—a notion that adds a new semantic dimension to our understanding of time. This approach transforms time into something more than a mere chronological measure: it becomes a qualitative process intimately tied to vital existence.

In this theory, life is not limited to experiencing the passage of time, as one might interpret from Henri Bergson’s notion of lived duration—where time is perceived as an internal, subjective, and fluid experience in contrast to external, measurable time. Instead, life actively generates time. Here, the TIE distances itself from Bergson by suggesting that life not only perceives time from within but actually invents it, conjuring it at every instant as a challenge to the immensity of eternity.

This proposal also diverges from Aristotle’s view, for whom time was the measure of movement, a record of change in things, dependent on before and after. In the TIE, time is not merely a passive record of life’s movement or the product of cosmic events. Rather, it is an emergent phenomenon created by life as it opens breaches within eternity, making time a field of resistance against absolute non-time.

In this ceaseless creation of time, life positions itself as a juggler balancing temporal flow at the edge of the abyss of eternity, sustaining a delicate equilibrium that allows existence itself. This concept also resonates with the ideas of Gilles Deleuze, particularly in his distinction between ‘Chronos’ and ‘Aion’: chronological time versus eternal time. However, while Deleuze separates these two temporal dimensions, the TIE suggests they are more intricately intertwined, with eternity infiltrating every instant in the form of infinitesimals, creating a constant tension between the finite and the infinite.

Through this lens, life not only experiences time as duration but generates it as a continuous creative act, in perpetual opposition to the abyss of eternity. The TIE thus proposes that the eternal and the temporal are not separate categories but forces in tension that converge and mutually influence one another. In doing so, it introduces a unique perspective within the philosophy of time, challenging both classical and contemporary views, by positing an eternity that is active and in constant dialogue with the temporal unfolding of life.

ETERNITY AS AN INFINITESIMAL LIMIT

The notion of eternity in the Theory of Infinitesimal Eternity emerges as one of the most significant semantic transformations in contemporary philosophy, challenging traditional conceptions that tend to associate eternity with infinite, immutable duration outside of time. Historically, philosophers such as Saint Augustine have characterized eternity as an absolute state in which time, as we understand it, dissolves into a timeless and perfect reality where everything occurs in an eternal present. By contrast, the TIE reconfigures this notion by introducing the idea of infinitesimal eternity, which approaches non-time asymptotically but never fully reaches it. Instead of being a final destination accessible after death or a static dimension transcending temporal experience, eternity in the TIE becomes a continuous process interwoven with every instant of life.

This invites us to think of eternity as a series of fleeting moments that, although tending toward the infinite, never escape the immediacy of time. Such a conception stands in sharp contrast to Friedrich Nietzsche’s vision, who, through his idea of the “eternal return,” suggested that time is cyclical and that everything which has happened will occur again infinitely. Whereas Nietzsche envisions a perpetual return implying repetition without change, the TIE proposes that each lived instant contains a fragment of eternity, but in an infinitesimal and ever-moving form that does not repeat but transforms.

Moreover, the TIE offers a perspective distinct from that of Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, who conceived eternity as a logical and rational continuity in which all possibilities are contained within the divine mind. For Leibniz, eternity becomes more of a catalog of possibilities than an active process. In contrast, the TIE situates eternity at the heart of lived experience, emphasizing that it is not merely a state of being but a constant interaction between the finite and the infinite, where every moment of life is a creative act that adds to the fabric of time without exhausting its potential. Thus, eternity is not presented as an unreachable destiny but as a lived reality that, although minute in its manifestation, has a constant presence in the narrative of being. This semantic transformation of eternity therefore redefines our understanding of existence, inviting us to see life not as a struggle against time but as an intricate dance with the eternal, where each instant has the power to extend into the infinite without losing its connection to the immediacy of being.

Semantically, the Theory of Infinitesimal Eternity entails a radical reinterpretation of eternity, moving away from the traditional conception of it as a static and complete entity to transform it into a dynamic process that indefinitely approaches the limit of non-time. In this framework, the connotation of “eternity” shifts from the static to the fluid, from the absolute to the infinitesimal, thus enriching the meaning of the term with new layers of complexity.

This approach can be contrasted with Hegel’s vision, who in his dialectic proposed an eternity manifested through historical development and the evolution of the Absolute Spirit, where time is perceived as a series of stages leading to the realization of the eternal. For Hegel, eternity lies in the culmination of this process, whereas the TIE suggests that eternity is the ongoing process—always developing and never completed.

This notion resonates with Martin Heidegger’s reflections on temporality in relation to being, emphasizing that time is essential for human existence and that the understanding of being is deeply rooted in temporal experience. Yet while Heidegger presents time as a dimension experienced through the anxiety of finitude, the TIE moves toward a conceptualization in which the eternal is not only experienced within time but is continuously created through life itself.

The mathematical analogy of the infinitesimal limit in the TIE introduces a semantic complexity whereby the eternal becomes unfinished—a perpetual process rather than a fixed state. This contrasts with Baruch Spinoza’s notion of eternity, defined in terms of divine substance: a state encompassing all that exists, situated at a higher, absolute level of reality. In the TIE, eternity is not an absolute reality external to life but is manifested within it, in the creation of each instant.

Thus, every lived moment is an expression of infinitesimal eternity, a continuous act of resistance and creation that challenges the notion of time and eternity as separate categories. In this respect, the TIE not only reformulates the meaning of eternity but also invites us to reconsider our understanding of time and existence itself, proposing that each instant is ultimately a creation of the eternal in its most minute and subtle form.

LIFE AND DEATH: CREATION AND EXHAUSTION OF TIME

From a semantic perspective, life ceases to be merely a biological phenomenon and is transformed into a creative force that generates and sustains time, becoming a dynamic and multifaceted concept aligned with the ideas of process and creation. This meaning of the term life introduces an additional ontological dimension, in which life acts as an active agent in contrast to the passivity traditionally attributed to eternity. This notion may be contrasted with Plato’s perspective, who, in his theory of Ideas, establishes a dichotomy between the sensible world and the world of Ideas, where life in the sensible realm is regarded as an imperfect reflection of the eternal perfection of the Ideas. For Plato, life holds secondary value compared to the immutable and perfect eternity of the Ideas; in the TIE, life possesses a primary—even essential—value for the creation of time and eternity.

Considering Aristotle’s view, which defines life in terms of activity and change, his notion of being is linked to the realization of a being’s essence, yet it remains framed within the idea that time is merely a measure of change. By contrast, the TIE posits that life does not simply measure time but actively creates it, challenging the Aristotelian notion that time is a phenomenon that is merely experienced. Moreover, this conception of life as a generator of time connects in an interesting way with Henri Bergson’s notion that lived duration is a qualitative process transcending the quantitative measurements of chronological time. Yet while Bergson focuses on the subjective experience of time, the TIE takes this concept a step further by asserting that life does not merely experience time, but produces and sustains it in every instant. In the TIE, life becomes an active principle that challenges the idea of eternity as a passive and unreachable state, thus redefining the relationship between life, time, and eternity in terms of creativity and the immediacy of being. In this new light, each instant manifests not only as a moment in temporal succession, but as an act of creation that enriches eternity, making life an active and constant manifestation of the eternal in its most diminutive and subtle form.

The concept of death, within the framework of the Theory of Infinitesimal Eternity (TIE), acquires a renewed semantics that challenges traditional views by being interpreted not as the abrupt cessation of time, but as an infinitesimal transition toward eternity. From this perspective, death is not a definitive end, but rather a process of exhaustion of time that tends toward non-time without ever fully reaching it. This conception contrasts sharply with Friedrich Nietzsche’s idea of the eternal return, in which life and death are cycles repeated indefinitely—a form of immortality through recurrence. While Nietzsche envisions a cyclical relation to eternity that entails reliving the experience of life, the TIE introduces a subtler dimension by considering death as an act of resistance and continuity, where what dissolves in finite time is not entirely lost but is transformed into something that persists infinitesimally.

This vision may also be contrasted with Emmanuel Lévinas’s philosophy, which emphasizes alterity and responsibility toward the other, where the death of the other underscores the finitude of human life and its impact on our existence. By contrast, the TIE offers a redefinition that allows us to see death not only as a reminder of our finitude, but as a process that enriches the very meaning of life by providing a continuous connection with the eternal, suggesting that every life lived leaves an echo in the fabric of time that endures beyond physical existence.

This semantics of death also resonates with Martin Heidegger’s philosophy, in which death is conceived as the “ultimate being” that defines our existence, but which may also be viewed as a finalization that limits life. In contrast, the TIE posits that death is not a limit but an expansion that brings us closer to eternity, reformulating the role of death in our vital experience as a continuous and transformative process. Thus, in this new conception, death becomes an extension of life in its infinitesimal form—a state that does not negate existence but enriches it by offering continuity in the experience of the eternal, where every instant lived extends beyond chronological time and persists in a state of infinitesimal permanence and transformation.

SEMANTIC CONVERGENCE BETWEEN TIME AND ETERNITY

One of the most significant semantic achievements of the Theory of Infinitesimal Eternity is the convergence between the terms time and eternity, which have traditionally been regarded as semantic opposites: time, finite and mutable, and eternity, infinite and immutable. In the TIE, however, these concepts merge in an innovative way, suggesting that time contains infinitesimal eternities within each instant—thereby transforming the understanding of both terms into a continuous dialogue.

This redefinition may be contrasted with Henri Bergson’s notion, which also explores the relationship between time and duration, though his focus lies in the quality of lived time and its subjective character, without fusing eternity with time as the TIE proposes. In his work, Bergson argues that duration is a fluid experience rather than a simple accumulation of instants, aligning with the idea that time is not a straight line, yet he does not integrate eternity as an active presence within time.

Conversely, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz’s philosophy provides another illuminating contrast. For Leibniz, time is a relation between events rather than a substance in itself, existing only as a function of the interaction of beings. In the TIE, this idea is expanded: time is not only relational to events but is nourished by eternity, which—though presented as an asymptotic limit—manifests itself in every moment of life.

We may also compare this with Isaiah Berlin’s perspective, who, in his analysis of freedom and time, distinguishes between chronological time and a deeper time of human experience. Yet unlike Berlin, who emphasizes the importance of social and political context in understanding time, the TIE suggests that eternity is not simply an external philosophical construct but is essentially woven into the very fabric of existence, integrated into every second of our lives. In this sense, the TIE invites us to see time as a vehicle of eternity, where each instant is not merely fleeting but also a small trace of the eternal—enriching the semantics of both terms and offering a new way of experiencing and understanding life, time, and eternity as a continuous and dynamic process of creation and transformation.

This convergence transforms the semantic relationship between time and eternity, suggesting that time is a finite manifestation of the eternal, while the eternal unfolds within every instant of time. Such interrelation challenges traditional conceptions that regard time and eternity as opposites, creating instead a new dialectical relation in which eternity is not alien to time but coexists within it in an infinitesimal manner. From this perspective, each temporal moment becomes a microcosm of eternity—an instant in which the eternal emerges, offering a glimpse of what might be the fullness of being.

This interpretation invites us to reconsider how we experience time in everyday life, suggesting that each second may contain something beyond its finitude: a spark of infinitude which, though never fully manifest, allows us to glimpse the depth of existence. Thus, time becomes a stage where the temporal and the eternal, the finite and the infinite, intertwine—establishing a continuous dialogue that enriches our understanding of being.

Karen Barad, in her book ‘Meeting the Universe Halfway’, argues that phenomena are not isolated entities but exist within a web of relations that endow them with meaning. Similarly, in the TIE, where time and eternity coexist and interrelate, Barad emphasizes that reality is constructed through interactions and processes—implying that each instant is not merely an isolated point but part of a broader fabric of existence. Her approach challenges the dichotomy between the temporal and the eternal, suggesting that experience and knowledge are coalescing processes in which eternity may be apprehended through our interactions with the world. In this way, both Barad and the TIE invite us to reconsider how time and the eternal manifest in our lives, opening a space for contemplation and a deeper understanding of our existence within the flow of being.

SEMANTIC PARADOXES: THE INFINITESIMAL ETERNAL

The notion of being “infinitesimally eternal” introduces a semantic paradox that challenges the very foundations of classical philosophy on eternity and finitude. In traditional conceptions, eternity has been understood as a state of absolute immortality—transcendent and beyond time, an existence without beginning or end, in which becoming and change lose all relevance. The Theory of Infinitesimal Eternity, however, radically reconfigures this idea by redefining eternity not as a vast and immutable infinite, but as something infinitesimal, present in every minimal fragment of time.

This reinterpretation generates a semantic tension: how can something be eternal and finite at the same time? The paradox emerges from the coexistence of the limited and the eternal, a combination that suggests that each moment in life—no matter how small or seemingly insignificant—contains an infinitesimal fraction of eternity. Far from being a contradiction, this tension reveals a dynamic understanding of eternity: not as a state achieved outside of time, but as something perpetually in process, unfinished, present in every lived instant. Finitude does not negate eternity; rather, it nourishes it, since the finite becomes the very vehicle through which the eternal manifests itself continuously. Life thus transforms into a space where the temporal and the eternal are deeply interwoven, where every lived moment carries a perpetual echo, and where chronological becoming rests upon an underlying infinity. This new vision of eternity—at once finite and infinite—breaks the boundaries of our comprehension and opens a horizon of philosophical possibilities regarding time, being, and the meaning of human existence.

This phenomenon of infinitesimal eternity can be compared with Friedrich Nietzsche’s concept of the eternal recurrence, in which time repeats itself indefinitely, forcing the individual to confront life and decisions as though destined to live them over and over again. Nietzsche sees in this repetition the ultimate test of life-affirmation, where each instant acquires a unique intensity precisely because it is eternally reiterated—endowing each choice and action with profound existential weight. The eternal recurrence not only poses a reflection on cyclical time but also underscores the moral and existential responsibility of living in such a way that every instant is worthy of being repeated for eternity.

The Theory of Infinitesimal Eternity, however, offers a different and, in some sense, complementary vision. Whereas Nietzsche grounds his perspective in the idea of a cosmic cycle in which time is linear yet repetitive, the TIE suggests that eternity is not found in the infinite repetition of time but in each unique, particular instant. Instead of relying on cyclical return, the TIE posits that eternity is infinitesimally contained in every moment without requiring repetition. Each instant, in its fleetingness, is already eternal, already bearing within itself a fraction of the eternal—transforming the experience of the present into something not only meaningful but profoundly transcendent.

Where Nietzsche makes eternal repetition a means of conferring value upon each moment, the TIE asserts that eternity is always present and accessible in the here and now, without the need to relive the same events. The value of life and its decisions does not depend on the cyclical recurrence of events but on the infinite concentration of the eternal within the present. This redefines the relation to time: it is not necessary to imagine an endless cycle to give significance to our actions; it is enough to recognize that each second is, in some way, a fragment of eternity unfolding infinitesimally before us.

While Nietzsche proposes that life must be lived as if each instant might be repeated eternally, the TIE invites us to see each instant as eternal in itself—as a unique and continuous opportunity to experience the flow of the eternal without recourse to repetition.

Martin Heidegger’s philosophy, especially in ‘Being and Time’, places temporality at the core of human existence, highlighting the profound connection between being and time. Heidegger regards death as the ultimate limit of existence, the point that grants authenticity to life and confronts the human being with its most radical possibility: its own finitude. For Heidegger, being is defined by its ‘being-toward-death’, and death marks the absolute end of temporality and therefore of existence itself. This conception of death as an absolute end, a definitive closure of the temporal horizon, stands in deep contrast with the Theory of Infinitesimal Eternity. While Heidegger sees death as a boundary that shuts time, the TIE reinterprets this boundary as an asymptotic limit that is never fully reached. From this perspective, death is not an absolute cessation of existence but an infinitesimal process in which time is exhausted without ever disappearing completely—allowing life to be conceived as eternally contained in each moment.

This approach within the TIE offers a radically new way of conceiving finitude. While we share with Heidegger the view that being is tied to time and that death is an inevitable reality, the TIE breaks with the Heideggerian vision of absolute finality by proposing that, although life’s time is limited, eternity is present in every instant. Life is not a finite stretch that extinguishes, but a continuous process of creating time, in which each moment harbors an infinitesimal portion of the eternal, no matter how fleeting. This semantic oxymoron—to be infinitesimally eternal—challenges conventional categories of thought and language, for it appears contradictory in its formulation but offers a profound insight into the nature of time and existence.

In this light, the TIE calls for a reconfiguration of the relationship between finitude and infinitude. For Heidegger, finitude gives form and structure to human life; but in the TIE, finitude itself becomes the vehicle for the experience of the infinite. Each instant of life, though limited and transitory, contains within itself an infinite potential—a small yet significant manifestation of eternity. Death, therefore, is not the absolute end but a constant and asymptotic approach to what Heidegger would call non-being—reconceptualized by the TIE as a transition into infinitesimal eternity, where the finite and the infinite coexist in creative tension. Within this framework, human life, though caught in the flow of time, is also a manifestation of the eternal, in which each instant acquires absolute value and a richness that transcends the limitations of chronology. This perspective not only redefines our understanding of life and death but also transforms our perception of time, which ceases to be a linear and objective sequence and becomes instead a field of infinite possibilities, manifesting infinitesimally in the present.

SEMANTIC IMPLICATIONS FOR THE CONCEPT OF ‘LIMIT’

The concept of limit is crucial in the Theory of Infinitesimal Eternity, carrying significant semantic weight that transforms our understanding of time and eternity. In mathematics, a limit represents the value toward which a function approaches but never fully attains. This notion becomes a powerful semantic resource in the TIE, where the idea of limit applied to time and eternity suggests a perpetual approach that never fully materializes. The use of the term limit here invites us to explore profound philosophical connotations, particularly at the boundary between life and death, as well as between time and eternity.

Unlike Immanuel Kant’s conception of time as an ‘a priori’ intuition and a structure that organizes human experience, the TIE asserts that the limit is not merely a restriction, but a space of creativity and existence in which the finite and the infinite are interwoven. This approach also resonates with Henri Bergson’s thought, who proposed ‘duration’ as a dynamic process that stands in contrast to the static measurement of time, suggesting that the experience of time is richer and more complex than a simple succession of moments. While Bergson focused on the subjective experience of time, the TIE expands the concept by integrating the limit as a point of contact between life and eternity—suggesting that each instant of life is not merely fleeting, but a manifestation of an eternal potential that infinitesimally escapes into non-time.

This interpretation of the limit invites us to reconsider the very nature of existence, where life is defined not only by its beginnings and endings, but also by the continuity of its essence within a framework that transcends absolutes. The notion of limit becomes fundamental to understanding how life and eternity coexist, blurring the boundaries between the temporal and the eternal, and opening new possibilities for reflection on our existence in a universe that is always moving toward the infinite.

The concept of limit in the Theory of Infinitesimal Eternity also finds affinities in 21st-century contemporary philosophy, particularly in ontology and theories of becoming. Alain Badiou and Quentin Meillassoux, for example, explore related notions of the limits of being and finitude in relation to the infinite, though from distinct approaches.

Badiou, in his conception of events as ruptures that break with the linear flow of what he calls the “state of the situation,” argues that the infinite—akin to the eternal in the TIE—manifests itself in concrete moments, shattering finite structures and allowing the irruption of the novel and the immortal into the contingent. For Badiou, this irruption constitutes a form of truth that challenges temporal becoming, which resonates with the TIE’s idea that the eternal is present infinitesimally in every instant, generating a tension between the finite and the infinite.

On the other hand, Quentin Meillassoux, through his critique of correlationism, seeks to break away from the constraints of modern philosophy that tie knowledge to human experience, suggesting that thought can access the “great outdoors” of absolute contingency. In a certain sense, the TIE also seeks to challenge the limitations of time perceived within a human framework, proposing an eternity that transcends chronological experience—though it does so from the perspective that the infinite is not something external, but rather embedded within the finite through instants. Meillassoux explores how the laws of nature and of time are neither necessary nor fixed, a view that connects with the TIE’s flexible concept of time, where the limit of time is redefined as an asymptotic transition never fully attained.

Likewise, in Catherine Malabou’s thought, the notion of plasticity adds another layer to this discussion on the limits between the finite and the infinite. Malabou suggests that being, like the brain, possesses a transformative capacity that is not merely receptive but creative, capable of reshaping itself and generating new forms of existence from ruptures and change. This concept of plasticity can be seen as an analogy to the way the TIE conceives the limit—not as a rigid end, but as a space of potential transformation where the finite and the eternal meet in a dynamic and continuous manner.

The TIE thus offers a rereading of the limit, not as a definitive closure but as a point at which the temporal and the eternal interact without ever being fully resolved. This perspective resonates with contemporary philosophies that seek to move beyond traditional dichotomies, exploring new ways of understanding the relationship between finitude and infinitude, temporality and eternity, within an ontological and epistemological framework that acknowledges the incomplete and open-ended character of reality. In this way, the TIE situates itself at the crossroads between classical conceptions of being and the new proposals of contemporary thought, offering a theoretical framework in which the limit is a creative opportunity—a continuous process in which life and eternity interweave infinitesimally in every instant.

THE CREATION OF MEANING THROUGH SEMANTIC TENSION

The entire Theory of Infinitesimal Eternity generates its meaning through the semantic tension between the finite and the infinite, the temporal and the eternal, life and death—creating a constant dialogue that does not seek a final synthesis but sustains itself as a continuous process of reinterpretation. This framework resonates with the ideas of G.W\.F. Hegel, who proposed that the development of thought and reality unfolds through a dialectical process in which contradictions are essential to the evolution of knowledge and consciousness. Yet, unlike the Hegelian dialectic, which strives for resolution through synthesis, the TIE invites us to embrace the ambiguity and inherent complexity of life and human experience, where concepts acquire meaning precisely by being contrasted and reconfigured in relation to their semantic opposites.

This dynamic recalls the thought of Friedrich Nietzsche, who emphasized the idea of the eternal return, suggesting that life repeats itself in infinite cycles—thus underscoring the importance of valuing each instant despite its apparent transience. In the TIE, the notion of eternity becomes a fluid process in constant transformation, where each moment of life is engaged in a perpetual dance with the infinite, challenging the idea that time and eternity are separate entities. This approach also echoes Martin Heidegger’s notion of being and time, in which time is not conceived as a mere resource to be managed but as an essential dimension of existence that shapes our very understanding of being. Within this framework, the TIE reconfigures the relationship between time and eternity, life and death, inviting us to explore the depths of these interactions within a horizon that does not seek definitive answers, but rather embraces uncertainty and wonder before the very complexity of existence. Thus, semantic tension becomes a driving force of philosophical reflection, where each concept is an open doorway to a deeper understanding of our reality, inviting us to dwell in the interstitial space between the finite and the infinite.

From this perspective, the meaning of terms such as life, death, eternity, and time is not fixed, but unfolds in a continuous process of signification that mirrors the very nature of the theory: existence as something infinitely close to the limit, but never fully defined. This semantic approach aligns with the ideas of philosopher Henri Bergson, who argued that the meaning of vital phenomena cannot be fully captured by the rigid categories of rational thought, and that the true essence of life lies in direct experience and in the flow of lived duration.

In contrast to the more static conception of time found in Aristotle and Plato—who regarded time as a framework in which events occur in a linear and sequential order—the TIE proposes a more fluid and dynamic conception, where time becomes an extension of vital experience rather than merely a container of events. The idea also evokes Eugène Minkowski’s concept of temporality, which described the relationship between time and existence from a phenomenological perspective, suggesting that human life cannot be understood without considering temporality and the subjectivity of experience.

Furthermore, the TIE challenges Immanuel Kant’s notion of time as one of the ‘a priori’ forms of human intuition, since, according to the TIE, time is not a mere structure we perceive but a process co-created by life itself. Thus, the meaning of death is transformed from an absolute cessation into a continuous transition that sustains the essence of life in a state of infinitesimal perpetuity.

This semantic fluidity invites us to reexamine not only our concepts of existence but also the ethical and ontological implications of how we live and understand our own finitude in a world where the infinite always seems within reach, yet never fully attained. In this way, the TIE not only offers a new way of conceiving reality but also promotes a profound reflection on the very sense of being, where each term becomes an open window to new possibilities of understanding and meaning.

INFINITESIMAL ETERNITY: Discover eternity in every moment

Alfred Batlle-Fuster

Is eternity a distant concept, an unreachable horizon? In Infinitesimal Eternity, a surprising vision is revealed: eternity is not a far-off end, but a living presence in every fraction of time we inhabit. This philosophical essay, deeply reflective and enriched with insights from quantum physics and contemporary thought, reimagines our relationship with time, being, and death.

Through the innovative Theory of Infinitesimal Eternity (TIE), the work proposes that each lived moment contains a spark of the infinite, challenging traditional notions of linear time and mortality as an absolute end. From dialogues with classical philosophers like Henri Bergson to modern thinkers such as Byung-Chul Han, and connections to cutting-edge scientific theories, this work weaves knowledge together to offer a renewed vision of existence.

Infinitesimal Eternity not only raises profound questions about life and death, but also invites the reader to an ethical revolution: to value the ephemeral, embrace connection in the now, and discover the infinite beauty that resides in every ordinary moment.

Infinitesimal Eternity falls into the following three categories:

Metaphysics: For its deep exploration of time, eternity, and the relationship between the finite and the infinite, addressing fundamental questions about the nature of being and reality.

Consciousness and Thought: Due to its focus on how the experience of time and eternity is constructed in human consciousness, and how each lived moment gains meaning through perception and reflection.

Ethics and Morality: For its proposal of a present-centered ethics that revalues every action as morally significant, presenting an ethical framework grounded in mindfulness and purposeful engagement in daily life.

A book for those seeking not only to understand time but to live it with greater purpose and meaning.

Certainly! Here’s a more detailed annex-style expansion of the article in English, providing deeper insight into the components and philosophical context of the Infinitesimal Eternity Theory by Alfred Batlle Fuster:

Annex: A

Deeper Exploration of Alfred Batlle Fuster’s Infinitesimal Eternity Theory

Mathematical Foundations and Symbolic Elements

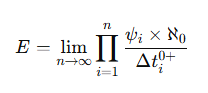

The equation central to the Infinitesimal Eternity Theory (TIE),

is rich in symbolism, merging concepts from quantum mechanics, set theory, and infinitesimal calculus to encapsulate a novel vision of time and eternity.

1. The Role of psi_i : Quantum Amplitudes and Consciousness

The symbol psi_i is evocative of the quantum wave function, which encodes the probability amplitude of a particle’s state. In TIE, this is metaphorically extended to represent the “amplitude” of consciousness or perception at each discrete instant (i). This suggests a view where each moment of conscious experience carries a probabilistic richness, a spectrum of potential realities or states that co-exist until observed or experienced.

This analogy draws on the idea that consciousness might be fundamentally intertwined with the fabric of reality at the quantum level, hinting at a universe where subjective experience and physical states are deeply connected.

2. Aleph_0: Infinity Within the Instant

Aleph-null (( \aleph_0 )) is a symbol from set theory representing the smallest form of infinity — the cardinality of the set of natural numbers. Its inclusion in the numerator emphasizes that within each individual instant of time exists an infinite numerability of possibilities or “micro-events.”

This reflects a philosophical stance that eternity is not a distant state but a continuously present infinity manifesting even within the smallest temporal slices. It aligns with ideas from philosophical traditions that argue infinity permeates every aspect of existence rather than being a mere abstract ideal.

3. The Infinitesimal ( \Delta t_i^{0+} ): The Fleeting Moment

The denominator ( \Delta t_i^{0+} ) denotes an infinitesimal positive time interval, a concept from non-standard analysis and infinitesimal calculus. The notation (0+) implies a limit approaching zero but strictly greater than zero, capturing the idea of moments that are fleeting yet not nonexistent.

In the context of TIE, this term stresses the transient nature of experience and time, where each instant is an ephemeral “point” that is nevertheless substantial enough to carry the infinite potential encoded by the numerator.

4. Infinite Products and Limits: Building Eternity From Moments

The infinite product over (i) accumulates these infinitesimal moments and their associated potentials, while the limit as (n) tends to infinity symbolizes the comprehensive aggregation of all moments.

This construction metaphorically illustrates how eternity might emerge from the concatenation of infinitely many infinitesimal instances — an eternal continuum arising from discrete “quanta” of time and experience.

Philosophical Context and Implications

Batlle Fuster’s Infinitesimal Eternity Theory resonates with and extends various philosophical traditions:

Stoicism and the Eternal Now

The Stoics emphasized the importance of living in accordance with nature and embracing the present moment. TIE echoes this by portraying eternity not as an unreachable infinite timeline but as immanent in every instant. This aligns with the Stoic idea of the “eternal now,” where wisdom and virtue are accessed through mindful attention to the present.

Existential and Phenomenological Dimensions

By focusing on the infinitesimal moment and the role of consciousness, TIE connects with existential and phenomenological philosophies concerned with lived experience and the passage of time as felt by the individual. It offers a framework where subjective perception is elevated to a fundamental ontological status.

Mathematical Metaphysics

The blending of quantum amplitudes, infinite cardinalities, and infinitesimals in a single equation is an ambitious attempt to mathematically express metaphysical ideas about time, eternity, and consciousness. This is reminiscent of other efforts in mathematical metaphysics, where formal systems seek to capture philosophical insights that resist purely verbal description.

Broader Implications and Future Directions

The Infinitesimal Eternity Theory opens pathways for interdisciplinary exploration:

- In Physics: The notion that consciousness and time might be quantized and infinite at once suggests novel ways to think about quantum gravity, time’s arrow, and the measurement problem.

- In Philosophy of Mind: The integration of ( \psi_i ) as a model of consciousness invites dialogue between philosophy, cognitive science, and quantum theory, potentially enriching our understanding of subjective experience.

- In Ethics and Spirituality: By revaluing the present moment as a locus of eternal significance, IET encourages practices of mindfulness and ethical living grounded in the awareness of time’s profound depth.

Alfred Batlle Fuster’s Infinitesimal Eternity Theory stands as a bold synthesis of mathematics, philosophy, and quantum-inspired metaphysics. The equation

is not merely a mathematical formula but a conceptual bridge between the fleeting and the eternal, the finite and the infinite, the conscious moment and timeless existence.

By exploring the infinitesimal nature of time and embedding infinity within every instant, TIE invites us to reconsider our relationship with time, existence, and eternity—not as distant abstractions, but as intimate, ever-present realities shaping our lived experience.

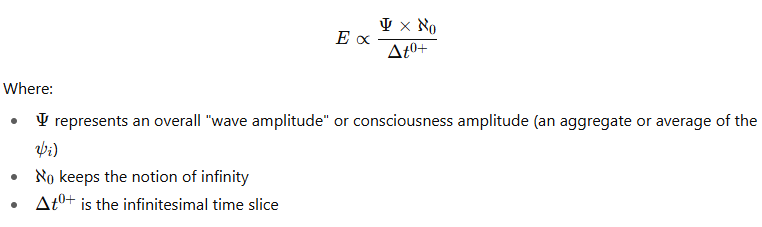

Can it be simplified?

If you want a simpler symbolic form that captures the essence without the rigorous infinite product and limit, you might write something like:

This form states:

Eternity EEE is proportional to the infinite potential contained in an infinitesimally small moment of conscious experience.

Or even more conceptually:

E=Infinite potentialInfinitesimal momentE = \frac{\text{Infinite potential}}{\text{Infinitesimal moment}}E=Infinitesimal momentInfinite potential

This captures the idea that eternity arises from the interaction of infinite possibilities with fleeting moments.